Chai and tea – what’s in a name?

Share

Languages have funny ways of evolving. The Czech word for ‘worker’ became the Afrikaans – and South African English – word for traffic light. ‘Consumption’ now the goal of a modern economy used to mean ‘wasting away’. Hence one would suffer from consumption when afflicted with what we now call Tuberculosis – the disease needing new nomenclature when economic growth assumed precedence. Denim Jeans – came from the French City of Nimes (de Nimes) and a similar rough spun from Genoa (Gênes en francais). From there it travelled to the workshop of Mr Levi Strauss on the shores of the Pacific. And beyond that to the hills on the bowed legs of tired miners and eventually to the most elegant limbs striding from the finest boutiques.

Much like this cloth of humble origins that went on to become a staple in our wardrobes a and the pinnacles of fashion, tea also emerged from obscurity, this time from the forests of Southern China to become the go-to in most kitchen cupboards. However, many tea words – including tea itself – have lost their true meaning along this lengthy journey.

We’re not prescriptive in how words should be used – much our own Rooibos, enjoy it how you like. Be yourself. We may do it a bit differently, but adding milk and sugar doesn’t affect us. We just like it without. Language is the same – as you long as they know what you mean, you’re fine. But, then again, it’s always good for you to know what you mean.

The first oddity is ‘fermented’ tea. Technically – i.e. in company when you need to say exactly what you mean – fermentation involves a biological process. The most well known of these being yeasts’ conversion of sugar into alcohol (technically ethanol, as alcohol is the whole group of chemicals). Tea’s transformation from green to black – or red in China – is more an oxidation than a true fermentation, although it is assisted by biological enzymes. However, the caveat on this is there are fascinating biological reactions taking place within the process. These do create the subtle flavours that provide intrigue, but it’s a small part of what’s going on.

Rooibos itself is often referred to as a tea. Yet, in more discerning company (where the author occasionally finds himself) tea refers only to the product of Camellia sinensis – ‘real’ tea. Rooibos, and it’s herbal cousins like yerba mate, Chamomile and the like are infusions, or perhaps tisanes. Referring to them as tea earning you a scolding – if not a scalding.

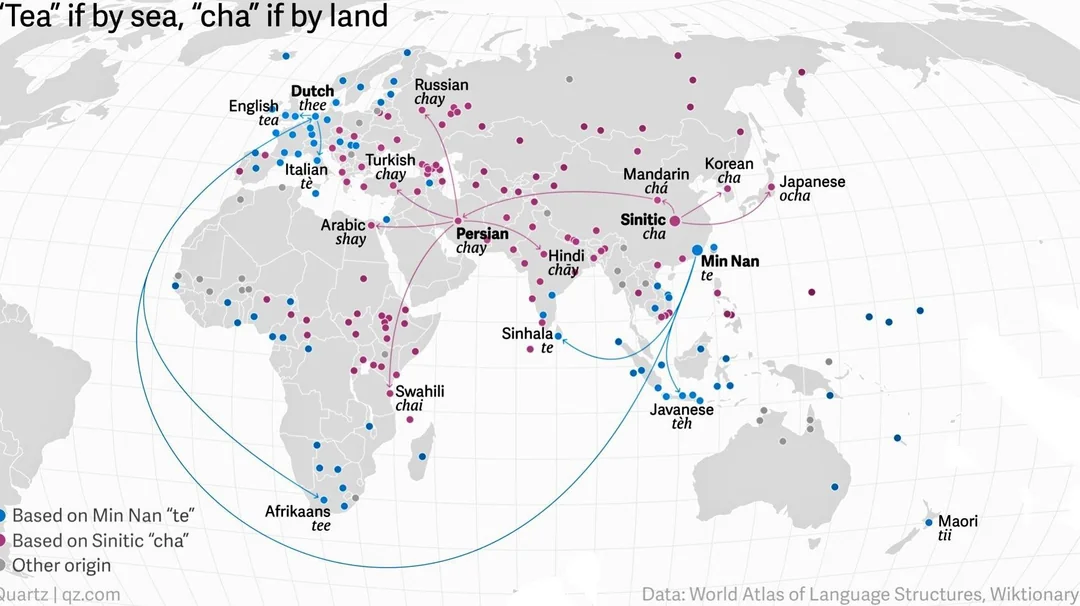

But what of ‘tea’ itself? We’ve seen above how so much loops back to China. Yet as tea spread its leaves across continents, the word for it was mostly ‘cha’ or similar. In Russian, Persian, and Turkish, tea does not exist, yet chai is central to the culture. Historically, the product, as well as its preferential term, came overland on camels. The Mandarins, who controlled these inland spice routes, used the word 茶 – pronounced ‘chá’. Yet, when the ships of European traders arrived on the coast of China – bypassing a continent’s worth of middlemen and perhaps after laying anchor in Cape Town (Hoerikwaggo in those days), they traded with the Fujianese or Amoi – who called it ‘te’. So most – but not all – Western European languages use a form of tea. Hence we have the expression, ‘tea if by sea.’ Interestingly, the exception to this were the first movers – the Portuguese – use ‘cha’ as they traded with a merchant from Guangdong – further South, close to where they would base themselves in Macau. So what do we mean when we say Chai tea? Does this not mean ‘tea tea’? Well, yes it does – which is why your Indian friend tries not to laugh when you say it. When caravans crossed the Himalayas laden with tea, the locals there soon began adding spices to it because… well, why not? The spicier forms of the beverage became popular and when the Europeans arrived with colonial ambitions, they asked what the brew was called and locals replied ‘well, chai’ – either not distinguishing between a spiced tea and a straight tea, or just dropping the (more technically) correct ‘Masala chai’. But what to do with all this new found knowledge? My suggestion is: not much. Treat it like that other widely traded leaf: put it your pipe and smoke it. Perhaps you’re like me and find the evolution of language interesting, but it is trivial. Some people do use words incorrectly, but the present context matters more than the historical precedent. Language is there to communicate a message. If you make yourself understood, you’re doing it well enough. If you’re writing a final exam, or hoping to impress a prospective boss or in-law, then maybe up your game, but otherwise: Relax. Chill out. Have a cup of tea. Just never a Chai tea.